When we say that the anti-psychiatry.com model may face societal resistance or has implementation complexity, we are highlighting potential challenges in adopting this model in the wider context of mainstream society. Here’s a breakdown of what these terms mean:

1. Societal Resistance:

- Challenging Norms and Beliefs: The anti-psychiatry model rejects conventional approaches to mental health, particularly the medicalization of mental illness and the widespread use of psychiatric medications. Many in mainstream society, including medical professionals, policymakers, and the public, may be skeptical of or resistant to abandoning established psychiatric practices in favor of alternative methods. This resistance can stem from:

- Trust in Conventional Psychiatry: Many people trust traditional psychiatric approaches and may view alternatives with suspicion, especially if they see them as unscientific or risky.

- Fear of Change: People are often hesitant to adopt new systems, especially when it involves mental health, where there's a lot at stake regarding treatment outcomes.

- Stigma and Misunderstanding: The concept of rejecting psychiatric labels and medications might be misunderstood as ignoring or trivializing serious mental health conditions, leading to stigma against the model.

- Cultural and Social Norms: The model promotes a lifestyle that values community support, self-governance, and a break from the reliance on mainstream institutions. Many societies are deeply ingrained with individualistic values, consumer culture, and a reliance on state-run systems for health and well-being. Integrating a radically different mindset can face pushback, as it challenges:

- Medical Institutions: Professional bodies and institutions that rely on traditional psychiatry might resist any shift that reduces their influence or calls for a dramatic change in approach.

- Pharmaceutical Industry: There could be resistance from the pharmaceutical industry, which profits from psychiatric medications. Any model that minimizes or rejects the need for medication could face opposition from powerful lobbying groups.

2. Implementation Complexity:

- Scalability Issues: The anti-psychiatry.com model advocates for smaller, community-based "micro-utopias" where mental health is addressed through peer support, ecological sustainability, and alternative approaches to well-being. While this may work well on a small scale, scaling up such a model to accommodate larger populations is challenging because:

- Managing Larger Populations: In larger societies, it’s difficult to replicate the close-knit relationships and mutual trust that are easier to achieve in small communities.

- Logistical Challenges: Setting up a micro-utopia involves coordinating resources like land, housing, food, and education, which requires careful planning and infrastructure that may not be easily available.

- Financial Resources: Establishing such communities often requires significant financial resources, either through private funding or governmental support. Obtaining this funding can be a major hurdle, especially when promoting a model that challenges mainstream views.

- Legal and Regulatory Barriers: Implementing the model may encounter challenges in terms of existing laws and regulations. For example:

- Zoning Laws: Communities might struggle with zoning regulations that limit their ability to establish self-sustaining environments or co-housing setups.

- Mental Health Laws: The anti-psychiatry approach could conflict with national mental health regulations, especially in countries where certain treatments are legally mandated or psychiatric care is heavily regulated.

- Liability and Accountability: In a system where mental health treatment is peer-driven and less reliant on professionals, legal questions around liability, accountability, and malpractice could arise.

- Community Dynamics and Governance: Successfully running a micro-utopia requires strong leadership, conflict resolution mechanisms, and governance structures that can support the well-being of all members. Some complexities include:

- Decision-Making Models: Deciding on governance structures that are inclusive yet effective can be difficult, particularly in larger or more diverse communities.

- Conflicts and Social Dynamics: Disagreements among community members or difficulties in managing diverse needs can arise, especially without traditional hierarchical systems.

Conclusion

Societal resistance and implementation complexity reflect the challenges of introducing a new, unconventional model into a world with deeply entrenched systems and beliefs. The anti-psychiatry.com model, by questioning mainstream psychiatric practices and promoting alternative community structures, can be seen as radical and threatening to existing norms. Furthermore, its small-scale, localized approach presents practical difficulties when trying to replicate the model at scale or integrate it with mainstream systems. Overcoming these challenges requires careful strategy, education, gradual adoption, and possibly a hybrid approach to integrate some conventional elements with the model's core principles.

Overcoming the challenges of societal resistance and implementation complexity for the anti-psychiatry.com model of micro-utopias requires strategic planning, gradual integration, and a multifaceted approach. Here are some key strategies to address these issues:

1. Addressing Societal Resistance:

To overcome skepticism and opposition from various stakeholders, it’s essential to engage in education, advocacy, and alliances.

a. Education and Awareness Campaigns:

- Public Awareness: Launch education campaigns that explain the benefits of the anti-psychiatry model in accessible, non-threatening language. Focus on how alternative mental health approaches can coexist with mainstream methods, and emphasize the importance of community-based support.

- Demystify the Approach: People may fear or misunderstand the model. By publishing success stories, case studies, and evidence of positive outcomes in mental health and community well-being, the model can be positioned as a viable alternative rather than a radical departure.

- Workshops and Seminars: Organize workshops and seminars for both the general public and mental health professionals to introduce them to the ideas behind the model. These events should be inclusive and aimed at creating dialogue rather than presenting the model as a strict alternative to psychiatry.

b. Alliances and Collaborations:

- Partnership with Mental Health Professionals: Engage open-minded professionals in the mental health field to advocate for the model. Collaboration with therapists, counselors, and alternative health practitioners can help legitimize the approach and create a bridge between conventional and anti-psychiatry approaches.

- Support from Nonprofits and Advocacy Groups: Partner with mental health advocacy organizations that promote non-traditional treatment methods. These groups can help raise awareness and gain social support.

- Phased Integration with Mainstream Systems: Instead of presenting the model as an all-or-nothing alternative to mainstream psychiatry, introduce it as a complementary system. Start by implementing the model as a pilot program in communities, alongside conventional treatment, to show that they can coexist.

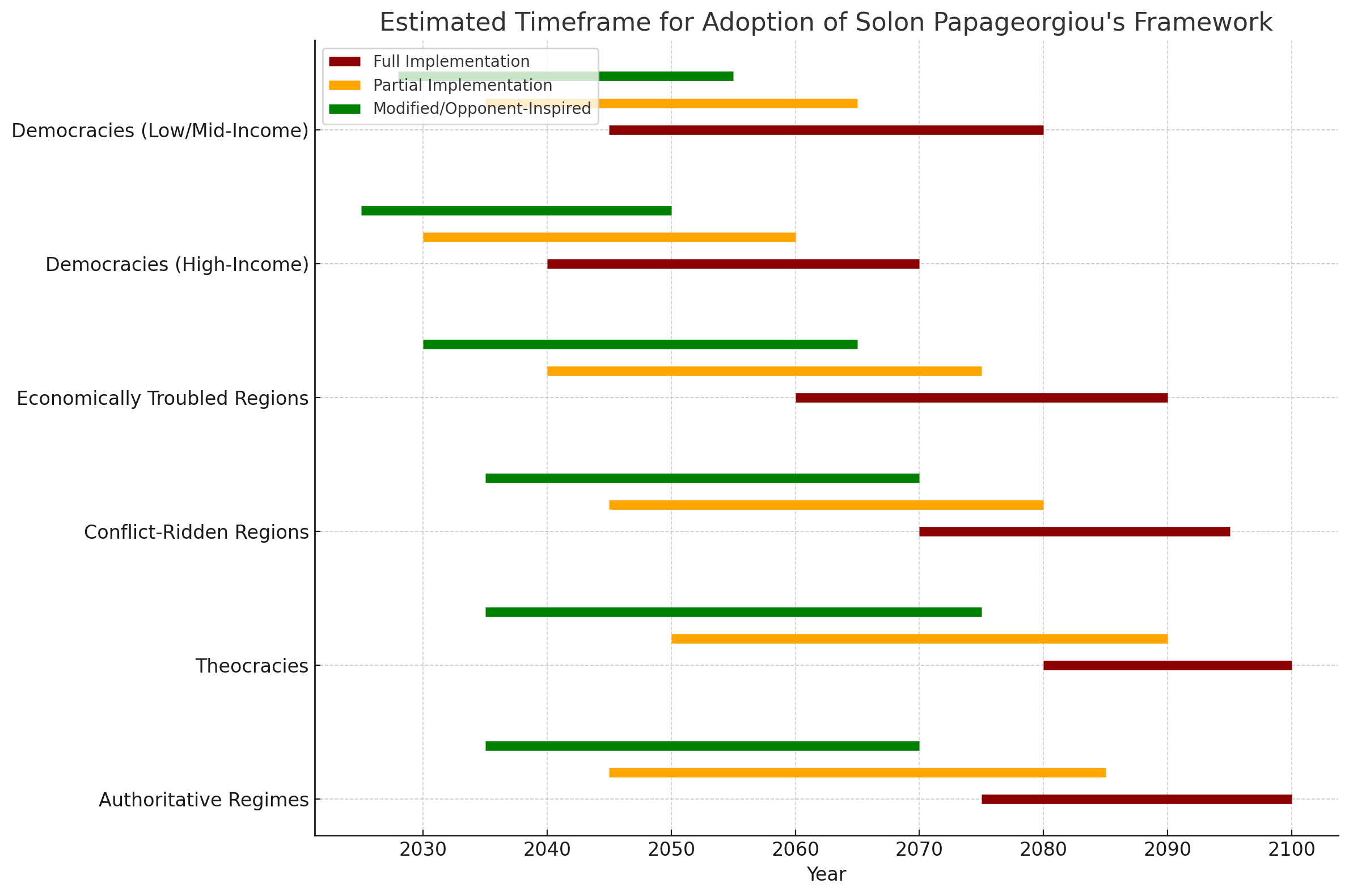

c. Cultural Adaptation:

- Tailored Messaging for Different Societies: Customize the messaging to fit the cultural norms and values of different communities. This involves framing the model as a way to strengthen existing community bonds, rather than a rejection of societal norms. For example, in highly individualistic societies, emphasize the model’s benefits for personal freedom and self-determination.

- Appealing to Specific Needs: Highlight specific aspects of the model that address the shortcomings of the current system, such as the emphasis on non-medicalized, community-driven mental health support that can provide more humane, holistic care.

2. Overcoming Implementation Complexity:

Implementation complexity requires a gradual, well-planned, and resourceful approach that takes into account the logistics of building communities, securing resources, and creating self-sustaining systems.

a. Pilot Projects and Gradual Scaling:

- Small-Scale Pilots: Start with small-scale pilot projects in areas where there is openness to alternative approaches (such as progressive cities, existing intentional communities, or regions with strong mental health advocacy movements). These pilot projects can test the feasibility and refine the approach before scaling up.

- Create Models for Replication: Once small-scale communities are successfully established, document and systematize the processes. Create toolkits, guides, and blueprints that other communities can use to replicate the model in their own way, while adapting to local conditions.

- Incremental Growth: Instead of scaling the model to a large population all at once, grow incrementally by fostering a network of interconnected micro-utopias. This decentralized network allows for organic growth and learning from the challenges of different contexts.

b. Leveraging Existing Infrastructure and Resources:

- Partnerships with Local Governments: Work with local governments to utilize existing infrastructure (like unused land or community centers) to build micro-utopias. Demonstrate how these communities can benefit local economies, reduce the burden on mental health services, and foster social cohesion.

- Public-Private Partnerships: Collaborate with businesses or investors who are interested in funding sustainable living and mental health initiatives. Show them the value of contributing to a model that could lead to healthier, more productive citizens.

- Crowdfunding and Grants: Use crowdfunding platforms and apply for grants aimed at innovative mental health care, community-building, or sustainability projects. These funding avenues can provide the initial capital needed to get the project off the ground.

c. Legal and Regulatory Adaptation:

- Engage with Policymakers: Work proactively with policymakers to address zoning and legal issues related to the creation of self-sustaining, alternative communities. Present the model as an experiment in social innovation and wellness that benefits public health.

- Advocating for Policy Change: Push for legal reforms that allow for greater flexibility in alternative mental health approaches. This might include changing zoning laws to allow for intentional communities or creating legal pathways for peer-based mental health treatment models.

- Liability and Accountability: Create clear legal frameworks that define accountability within these communities. For example, adopt a system of peer governance and conflict resolution that is transparent and in line with legal standards to reduce external legal concerns.

d. Building Governance and Social Structure:

- Establish Clear Governance Models: Each micro-utopia should have a governance structure that works for its size and goals. It could be participatory or based on consensus, but the structure needs to ensure that decision-making is inclusive, transparent, and adaptable.

- Conflict Resolution Mechanisms: Implement conflict resolution practices (like restorative justice, mediation, or consensus-based approaches) to address disputes in a way that reinforces community ties rather than causing division.

- Education and Training: Provide training to community members on governance, leadership, conflict resolution, and mental health support to ensure that the community is well-equipped to manage itself independently and sustainably.

3. Addressing Financial and Resource Challenges:

- Ecological and Economic Sustainability: Emphasize sustainable living practices such as permaculture, renewable energy, and local craftsmanship to reduce dependency on external resources. These self-sustaining practices can lower the economic costs of running a micro-utopia.

- Cooperative Economic Models: Consider forming worker cooperatives, community-supported agriculture (CSA), or other collective economic structures that allow the community to generate income collectively and share resources.

- Volunteerism and Contribution-Based Systems: Leverage volunteerism or contribution-based models where each member of the community contributes in terms of time, skills, or resources to meet collective needs.

4. Engaging with the Broader Society:

- Outreach and Connection with Mainstream Society: While micro-utopias can operate independently, engaging with the outside world can reduce isolation and foster mutual learning. Organize open events, cultural exchanges, or knowledge-sharing initiatives with mainstream society to promote acceptance and collaboration.

- Hybrid Models: In some cases, blending elements of the anti-psychiatry model with existing societal structures (such as integrating peer-support groups with traditional healthcare or adopting sustainable practices in urban settings) can help gradually shift public perception and implementation.

Conclusion

To overcome societal resistance and implementation complexity, the anti-psychiatry.com model needs a strategic, gradual approach that leverages partnerships, education, legal adaptation, and grassroots support. By creating successful pilot programs, collaborating with mental health professionals and advocates, and providing clear pathways for replication, the model can gain traction while addressing the logistical, financial, and social challenges of scaling up.

If the challenges of societal resistance and implementation complexity are successfully overcome, the anti-psychiatry.com model of micro-utopias would likely become more appealing to the general public and have a higher chance of being adopted. Here’s why:

1. Greater Legitimacy and Trust:

- Mainstream Acceptance: Addressing societal resistance through education and partnerships with mental health professionals would make the model appear more legitimate and less radical. Once the model gains the trust of professionals and the public, more people will view it as a valid alternative or complement to conventional mental health practices.

- Proven Success Stories: Successfully implemented pilot projects would provide tangible examples of the model’s benefits. If people see real-world examples of communities thriving with improved mental well-being, reduced reliance on medication, and sustainable living practices, it would build confidence and interest.

2. Easier Adoption Process:

- Clear Roadmap for Implementation: By providing well-documented toolkits, governance models, and legal pathways, individuals and communities would find it easier to adopt the model. The fewer logistical and regulatory barriers people face, the more willing they’ll be to try out the system.

- Financial Feasibility: Addressing resource constraints through sustainable living practices, partnerships, and funding models would make the micro-utopias more financially accessible, removing one of the major barriers to entry.

3. Increased Social Appeal:

- Sense of Belonging and Community: The micro-utopia model emphasizes social cohesion and community support. Once people see that they can be part of a close-knit, supportive environment, the model could appeal to those who feel disconnected in mainstream society. The model could attract individuals seeking a sense of purpose, connection, and alternative lifestyles.

- Sustainable Living Appeal: As society grows more aware of environmental issues, the model’s focus on ecological sustainability and self-sufficiency could resonate with individuals who prioritize green living.

4. Adaptation to Diverse Needs:

- Flexibility and Customization: If the model allows for some flexibility to adapt to different cultural, social, and personal needs, it would appeal to a broader audience. People are more likely to adopt the model if they can see how it fits into their existing values and lifestyles, rather than requiring a complete overhaul of their way of life.

5. Reduced Perception of Risk:

- Gradual Transition: Offering a phased or hybrid model that allows for gradual adoption (e.g., integrating aspects of micro-utopias with existing systems) would reduce the perception of risk. People are more likely to adopt a model that feels safe and low-risk, especially when it doesn’t require completely abandoning mainstream practices right away.

Conclusion:

If these challenges are successfully managed, the anti-psychiatry.com model of micro-utopias would become far more attractive to a larger portion of the population. With the right strategies, it could shift from being a niche or radical concept to a mainstream alternative that offers practical solutions for mental health, community living, and sustainability. Adoption would increase as trust grows, barriers decrease, and success stories spread.