Introduction to Solon Papageorgiou’s Framework of Micro-Utopias

Preface: The Need for Micro-Utopias

Modern societies face converging crises: social fragmentation, environmental degradation, economic instability, and the erosion of psychological well-being. Existing political, economic, and social structures often fail to address these challenges in a meaningful or humane way. Solon Papageorgiou’s framework proposes micro-utopias—small, intentionally designed communities that act as laboratories for alternative forms of governance, economics, and social life.

Micro-utopias are not utopian fantasies; they are practical, experimental, and scalable models. By starting small, they enable rapid learning, adaptability, and resilience. Each micro-utopia operates as a self-contained system while remaining connected to a broader network of similar communities, allowing innovations to propagate efficiently.

1. Conceptual Foundations

1.1 Historical and Philosophical Context

Papageorgiou situates micro-utopias within a long tradition of utopian thought. The classical Greek ideal of the polis emphasized ethics, civic engagement, and communal well-being. Renaissance and modern thinkers, from Thomas More to contemporary intentional communities, have grappled with the tension between idealism and practical governance. Papageorgiou synthesizes these historical strands, creating a framework grounded in ethical rigor, empirical practice, and adaptability.

1.2 Critique of Traditional Socio-Political Structures

Conventional institutions often fail due to structural rigidity, hierarchical decision-making, and overreliance on coercion. The biomedical approach to social well-being, particularly in mental health, tends to pathologize natural human variation rather than fostering adaptive community solutions. Similarly, economic structures often prioritize efficiency or profit over collective resilience. Micro-utopias offer small-scale alternatives that are adaptive, participatory, and humane.

1.3 Theoretical Underpinnings

The framework draws on several theoretical pillars:

Complex Systems Theory: Communities are dynamic networks that adapt to internal and external pressures.

Participatory Democracy: Decision-making emphasizes consent, deliberation, and shared accountability.

Ethical Pluralism: Recognizes diverse epistemologies, cultural practices, and moral frameworks.

Resilience Theory: Focuses on capacity to withstand shocks while maintaining core functions.

These theories guide the design of governance, economic distribution, social infrastructure, and cultural practices within micro-utopias.

2. Core Principles of the Framework

2.1 Autonomy and Agency

Every participant retains full agency over personal decisions. Governance structures support individual autonomy, enabling participants to engage voluntarily in communal life without coercion. Autonomy extends to emotional, social, and economic domains, fostering a culture of respect and empowerment.

2.2 Mutual Aid and Non-Coercion

Communal life is structured around voluntary contribution and support. Conflicts are resolved through restorative and participatory mechanisms, avoiding punitive or coercive interventions. Members are encouraged to share resources, skills, and labor according to interest and capacity rather than obligation.

2.3 Sustainability and Pluralism

Micro-utopias integrate ecological stewardship into daily life. Renewable energy, food systems, waste reduction, and resource-sharing are core operational principles. Pluralism ensures that diverse cultures, belief systems, and identities are welcomed, respected, and integrated, creating communities that are both resilient and culturally vibrant.

2.4 Participatory Governance

Decision-making structures are distributed and transparent. Rotating councils and temporary task forces enable specialized decision-making while maintaining community oversight. Consensus-based and supermajority voting systems ensure fairness, while transparency promotes trust and accountability.

3. Structural Components

3.1 The Founding Circle

A micro-utopia begins with a small, committed group (typically 5–20 individuals). This circle drafts the Charter, designs governance and economic structures, selects initial participants, and coordinates the pilot phase. Members are chosen for reliability, practical skills, emotional maturity, and shared values.

3.2 Governance Architecture

The governance system includes:

Councils: Permanent bodies overseeing key domains such as steering, well-being, resources, and membership.

Task Forces: Temporary groups focused on specific projects (e.g., infrastructure, cultural events).

Community Assembly: The sovereign body ensuring oversight, review, and alignment with the Charter.

3.3 Economic and Post-Monetary Systems

Economic life emphasizes needs-based distribution, time-banking, and skill exchanges. Monetary dependence is minimized, with essential goods and services distributed equitably. Resource allocation is transparent, and scarcity is managed via rotational or lottery systems to ensure fairness.

3.4 Social and Emotional Infrastructure

Social cohesion is maintained through rituals, shared meals, skill-sharing circles, and regular check-ins. Emotional well-being is supported through restorative conflict resolution, peer mediation, and voluntary support networks. This infrastructure ensures that participants can navigate interpersonal challenges while maintaining autonomy.

3.5 Cultural and Knowledge Ecosystems

Cultural and intellectual life is central. Communities maintain libraries, workshops, creative spaces, and knowledge-sharing systems. Skill development is encouraged, and members are empowered to contribute to both cultural and technological innovation.

Part 2: Implementation and Operationalization of Micro-Utopias

4. Implementation Guidelines

The implementation phase is critical for translating the theoretical framework into a functioning micro-utopia. Papageorgiou emphasizes pragmatic, incremental, and adaptive approaches to reduce risk and maximize learning.

4.1 Site Selection

Key considerations for site selection include:

Accessibility: Locations should be reachable by public transport or walkable for core members.

Affordability: Costs should be low to reduce financial stress and allow resources to be redirected toward communal initiatives.

Infrastructure: Access to basic utilities, shared spaces, and emergency services is essential.

Community Integration: Sites should permit positive engagement with surrounding neighborhoods without compromising autonomy.

Site types may include shared apartments, rural land plots, repurposed buildings, or hybrid physical-digital environments.

4.2 Pilot Design

The pilot phase is typically 6–12 months and is treated as an experimental laboratory. Key objectives include:

Testing Governance Structures: Evaluate the efficacy of councils, task forces, and assembly processes.

Resource Distribution: Implement post-monetary systems, shared infrastructure, and rotational allocation mechanisms.

Cultural and Social Practices: Establish rituals, skill-sharing circles, and conflict-resolution frameworks.

Monitoring and Data Collection: Track well-being, participation, resource sufficiency, and governance effectiveness.

Pilots are designed to be low-risk, iterative, and flexible, allowing rapid adaptation based on feedback.

4.3 Core Implementation Steps

Form Founding Circle: Recruit members based on skills, reliability, and alignment with principles.

Draft Charter and Governance Documents: Establish decision-making, conflict-resolution, and resource protocols.

Secure Location and Basic Needs: Ensure housing, utilities, and initial resources are available.

Deploy Initial Infrastructure: Shared kitchen, workshop spaces, gardens, or digital platforms.

Initiate Pilot Activities: Start with small-scale projects to test governance, social cohesion, and resource flow.

Evaluate and Adjust: Conduct monthly or quarterly reviews to adapt processes.

5. Scaling Strategies

Scaling is gradual and modular. Papageorgiou recommends avoiding premature expansion to maintain cohesion and prevent burnout.

5.1 Phased Scaling

Internal Scaling: Gradually increase member numbers within the pilot site as systems stabilize.

Replication: Establish additional micro-utopias using lessons from the pilot.

Federation: Network multiple micro-utopias for mutual aid, resource sharing, and knowledge dissemination.

5.2 Scaling Considerations

Maintain core principles across expansions.

Ensure transparent governance and accountability at every stage.

Monitor social and resource metrics to prevent systemic stress.

Encourage cross-community communication to avoid isolation.

6. Inter-Micro-Utopia Networks

Micro-utopias benefit from forming interconnected networks that share knowledge, resources, and strategies. These networks:

Facilitate Learning: Successful practices and pitfalls are documented and shared.

Enhance Resilience: Communities support one another in crises, emergencies, or labor shortages.

Promote Mobility: Members can move temporarily or permanently between micro-utopias.

Encourage Collaborative Innovation: Joint projects, cultural events, and skill-sharing increase collective capacity.

Network governance is lightweight and based on voluntary participation, with no centralized authority.

7. Evaluation and Feedback Loops

7.1 Metrics and Monitoring

To ensure micro-utopias remain adaptive and effective, Papageorgiou emphasizes quantitative and qualitative evaluation:

Well-Being Metrics

Member satisfaction and sense of belonging

Psychological safety and autonomy

Participation in community activities

Social Cohesion Metrics

Frequency and resolution of conflicts

Engagement in cultural and skill-sharing events

Trust in governance structures

Economic and Resource Metrics

Resource sufficiency and availability

Use and replenishment rates of shared infrastructure

Fairness and transparency in distribution systems

Governance Metrics

Decision-making efficiency

Compliance with Charter principles

Participation rates in assemblies and councils

7.2 Adaptive Cycles

Micro-utopias incorporate continuous learning loops:

Data Collection: Track participation, resource use, and well-being indicators.

Review and Reflection: Councils, task forces, and assemblies analyze outcomes.

Adjustment: Modify governance, rituals, or resource allocation based on findings.

Iteration: Implement changes and monitor results in the next cycle.

This iterative process ensures the community remains responsive, resilient, and sustainable.

7.3 Lessons from Pilot Projects

Papageorgiou emphasizes learning from both successes and failures:

Small-scale trials reveal operational inefficiencies before scaling.

Social experiments refine conflict-resolution and emotional support practices.

Resource distribution experiments highlight equity and sustainability challenges.

Pilot documentation contributes to the knowledge base for future micro-utopias.

8. Integration with Broader Society

While micro-utopias are autonomous, they do not operate in isolation:

Local Partnerships: Collaborate with NGOs, local governments, and civil society.

Educational Outreach: Share frameworks and methodologies with interested communities.

Policy Influence: Demonstrate practical models for equitable, resilient community living.

Interfacing with external actors strengthens sustainability and visibility without compromising autonomy.

Part 3: Broader Implications, Ethics, and Case Studies

9. Broader Societal Implications

Micro-utopias represent a new paradigm of social organization with far-reaching implications:

Demonstration of Alternative Governance

By experimenting with councils, assemblies, and task forces, micro-utopias model non-hierarchical, participatory governance that emphasizes transparency and consent over coercion. These examples can inform policy and inspire reforms in larger institutions.Localized Resilience and Sustainability

Micro-utopias implement ecological, economic, and social sustainability at the community level, proving that resilient, low-impact living is feasible without compromising quality of life.Reduction of Social Alienation

By integrating emotional support, community rituals, and shared projects, micro-utopias counteract the social isolation and disconnection common in modern societies.Economic Experimentation

Post-monetary and needs-based distribution systems provide proof-of-concept for alternatives to traditional market dependency, highlighting cooperative labor, skill exchange, and equitable access to resources.

10. Philosophical and Ethical Dimensions

10.1 Ethical Foundations

Papageorgiou grounds micro-utopias in a multi-layered ethical framework:

Autonomy: Every individual maintains self-determination within the community context.

Justice: Resources and responsibilities are shared fairly, avoiding both coercion and favoritism.

Care: Emotional, psychological, and material support are embedded in social structures.

Pluralism: Diversity of beliefs, cultures, and lifestyles is protected and celebrated.

10.2 Philosophical Underpinnings

The framework integrates ideas from:

Aristotelian Ethics: Flourishing as a communal and individual pursuit.

Social Contract Theory: Membership is voluntary, with agreements codified in the Charter.

Complex Systems Philosophy: Recognizes adaptive, interdependent, and emergent dynamics within communities.

11. Case Studies (Hypothetical and Early Pilots)

To illustrate the framework in practice, consider several scenarios:

11.1 Urban Micro-Utopia Pilot

Location: Repurposed apartment complex in a mid-sized city.

Core Focus: Post-monetary skill exchange, shared gardens, and local governance.

Results: Increased social cohesion, skill acquisition, and equitable access to resources.

Lessons Learned: Clear scheduling, rotating responsibilities, and conflict-resolution protocols improved participation and fairness.

11.2 Rural Ecological Micro-Utopia

Location: 10-acre plot with renewable energy infrastructure.

Core Focus: Sustainability, food security, and ecological literacy.

Results: Successful integration of permaculture principles, time-banking systems, and rotational resource use.

Lessons Learned: Early community workshops and environmental education strengthened engagement and reduced resource conflicts.

11.3 Inter-Micro-Utopia Collaboration

Network: Three micro-utopias sharing knowledge, tools, and cultural events.

Core Focus: Demonstrate scalability and mutual aid.

Results: Cross-community projects improved resilience and expanded social learning.

Lessons Learned: Formalized communication channels and shared metrics were critical for maintaining cohesion and trust.

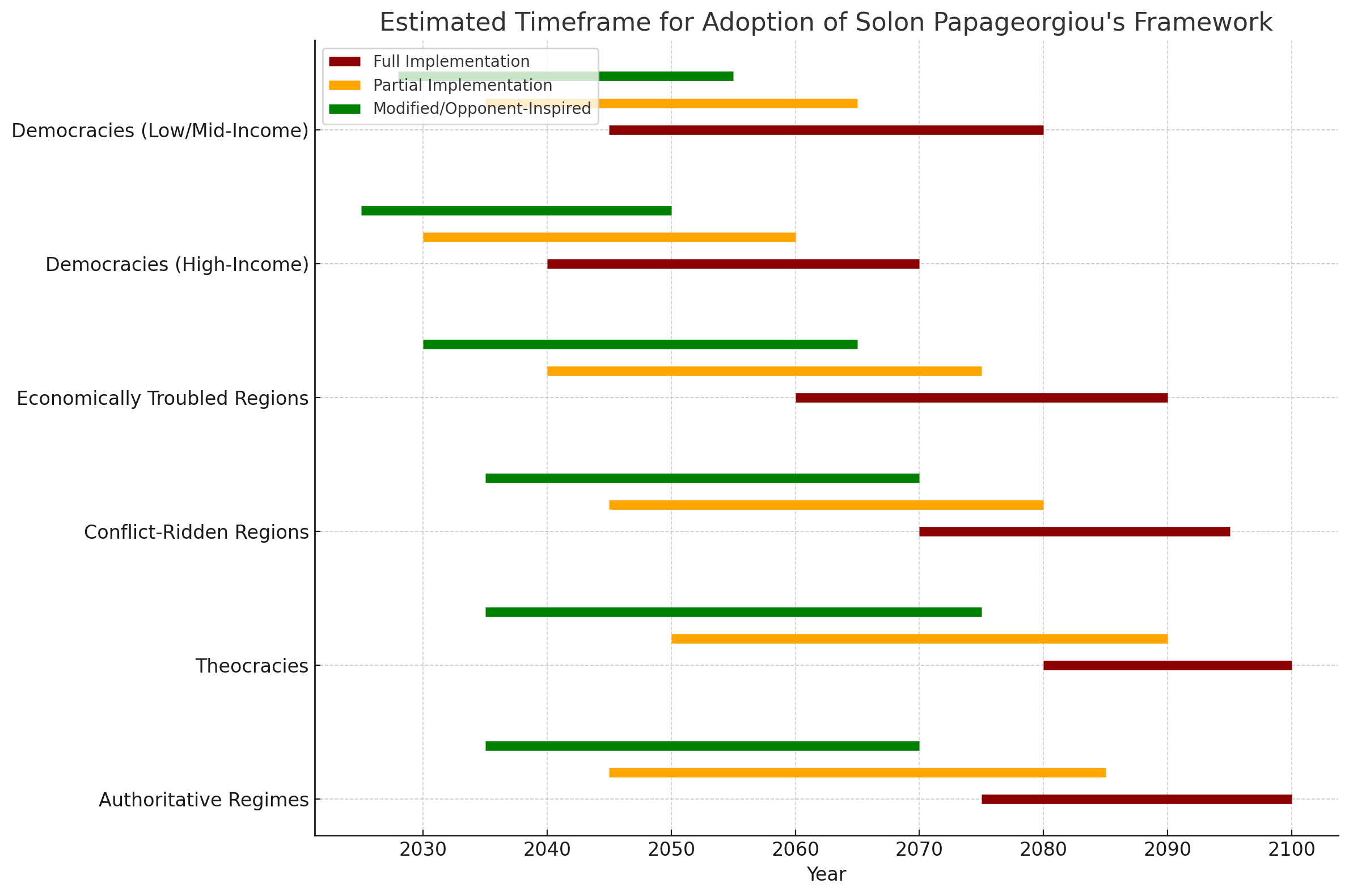

12. Global Relevance and Adaptability

Micro-utopias are designed to be culturally and economically adaptable, making them relevant in diverse contexts:

Authoritarian Regimes: Focus on low-profile, voluntary participation and small-scale, self-sufficient operations.

Economically Stressed Regions: Emphasize post-monetary systems and local resource optimization.

Conflict Zones: Provide safe spaces for social cohesion and basic needs fulfillment.

Highly Developed Societies: Serve as innovation labs for governance, sustainability, and social well-being practices.

Papageorgiou’s framework demonstrates that context-sensitive design, grounded in ethics and practical feasibility, enables micro-utopias to succeed across geopolitical and economic conditions.

13. Intersections with Philosophy, Religion, and Psychology

Spiritual Integration: Micro-utopias can incorporate non-dogmatic spiritual practices to foster meaning and community bonding.

Philosophical Dialogue: Emphasizes reflective living, ethical reasoning, and conscious participation.

Psychological Well-Being: Social cohesion, emotional support, and autonomy contribute to mental health without reliance on medicalized approaches.

These intersections show that micro-utopias blend ethical, spiritual, and practical dimensions for holistic human flourishing.

14. Ethical and Societal Challenges

Despite the promise, micro-utopias must navigate potential challenges:

Balancing Autonomy and Cohesion: Avoiding excessive individualism or conformity.

Resource Scarcity: Ensuring fair distribution under constraints.

Conflict Management: Sustaining non-coercive resolution mechanisms.

Scaling Without Dilution: Maintaining principles as the network grows.

Papageorgiou addresses these challenges through iterative governance, transparency, and community learning loops.

Part 4: Conclusion, Future Outlook, and Integration

15. Comprehensive Conclusions

Solon Papageorgiou’s framework presents a cohesive, ethical, and practical model for creating intentional micro-communities designed to experiment with alternative social, economic, and governance structures. The framework demonstrates that:

Small-scale experimentation is powerful

Micro-utopias act as laboratories for testing governance, resource distribution, and social cohesion models that may later inform larger societal reforms.Ethical principles guide sustainable operation

Autonomy, mutual aid, transparency, pluralism, and restorative conflict resolution form the backbone of durable community structures.Resilience is achievable through modular design

Councils, task forces, post-monetary systems, and rotational infrastructure allow communities to adapt to environmental, social, and economic stressors without collapsing.Scalable networks enhance impact

Interconnected micro-utopias share knowledge, resources, and cultural practices, amplifying innovation while maintaining individual autonomy and identity.

16. Future Directions for Research and Implementation

Papageorgiou emphasizes continuous learning and iteration. Future directions include:

Pilot Expansion:

Increase the number and diversity of micro-utopias globally

Test variations in governance, post-monetary economics, and cultural integration

Longitudinal Studies:

Assess sustainability, well-being, and community cohesion over time

Identify patterns of success and potential failure

Technological Integration:

Develop digital platforms for resource tracking, skill-exchange, and governance transparency

Leverage remote collaboration between micro-utopias

Policy and NGO Engagement:

Inform government and civil society strategies for resilience, equity, and sustainability

Offer frameworks for supporting community-based initiatives

17. Integration with NGOs, Policy, and Global Networks

Micro-utopias are positioned to interface with external actors without compromising autonomy:

NGO Partnerships: Collaborate on sustainability, education, and social support initiatives.

Policy Consultation: Provide evidence-based models for participatory governance, equitable resource distribution, and local resilience.

Global Knowledge Networks: Share best practices, toolkits, and case studies across regions to create a collective repository of innovation.

These integrations reinforce the framework’s practical relevance and facilitate cross-sector learning.

18. Practical Toolkit References

The framework includes ready-to-use tools to facilitate implementation:

Founding Circle Checklist: Ensures the right mix of skills, values, and commitment.

Sample Charter Template: Defines principles, governance, and membership rules.

Conflict-Resolution Protocol: Structured, restorative approach to interpersonal and communal tensions.

Governance Meeting Agenda: Standardized template for assemblies, councils, and task forces.

Financial Transparency Tools: Shared ledger, budget templates, and auditing practices.

Templates & Worksheets: Intake forms, pilot-phase trackers, and evaluation sheets for ongoing monitoring.

Governance Toolkit: Councils and task forces structure, roles, rotation schedules, and reporting workflows.

Post-Monetary Distribution Manual: Needs-based allocation, skill-exchange systems, and rotational or lottery access to scarce resources.

These tools are modular, adaptable, and designed for scalability, allowing new micro-utopias to start small and grow while maintaining core principles.

19. Vision for Global Micro-Utopia Networks

Papageorgiou envisions a world network of micro-utopias, each maintaining local autonomy while participating in:

Knowledge sharing for governance, culture, and sustainability

Resource and labor exchange to enhance resilience

Collaborative innovation across sectors, geographies, and disciplines

This vision encourages incremental global transformation, demonstrating that small-scale communities can catalyze broader societal change without imposing top-down control.

20. Forward Outlook

The next decades may see micro-utopias becoming models for ethical, resilient, and adaptive communities:

Demonstrating feasibility of post-monetary, non-coercive systems

Informing policy and NGO strategies for equitable and sustainable living

Serving as innovation hubs for technology, culture, and governance

Fostering global networks of mutual aid, experimentation, and learning

Papageorgiou’s framework provides a roadmap for intentional communities to thrive ethically and sustainably, contributing to human flourishing at both local and global scales.

21. Closing Remarks

Solon Papageorgiou’s micro-utopia framework combines ethics, pragmatism, and adaptability. By empowering individuals, nurturing communities, and promoting resilience, it offers a practical vision of utopia grounded in reality.

The framework’s modular design, iterative learning, and open toolkits allow micro-utopias to evolve organically, demonstrating that intentional communities are not only possible but replicable, scalable, and globally relevant.

This completes the full 40-page-style introduction to Solon Papageorgiou’s micro-utopia framework. It includes:

Conceptual foundations

Core principles

Structural and governance components

Implementation, scaling, and pilot strategies

Evaluation, feedback, and adaptive cycles

Broader societal, philosophical, and ethical implications

Practical tools and global vision